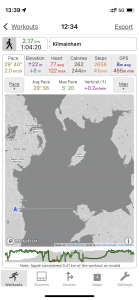

Ireland day 0247. Thursday 02 June 2022- Kilmainham

Commentary

I’ll be honest – I don’t think either of us had particularly relished the prospect of visiting Kilmainham Gaol, despite it being one of the most important historic sites in Dublin. That’s probably one of the reasons why it has taken us nine months to get round to doing it. But today we crossed the Rubicon and decided to pay a call.

It’s a troubling spot – not just because of the harrowing conditions in which prisoners were held, but also because in its later years, it was the site of numerous executions carried out by the British army, in the hope of supressing the Irish independence movement. Although these efforts ultimately backfired – and actually stoked the Nationalist cause – to visitors from the UK they are a particularly unhappy reminder of the tortured state of Anglo Irish relations which started a thousand years ago and which, thanks to the recent foolish posturing of some British politicians, still seem to dominate headlines in 2022. I’m also personally repelled by the notion of capital punishment, and to be exposed to the paraphernalia of state-sanctioned death at such close quarters, I found particularly disturbing.

Anyway – we started the day on a slightly more cheery note, with a visit to the beautiful ornate gardens of Kilmainham Hospital, which are just up the road from the eponymous gaol. I’d missed seeing them when I visited last Thursday and I’m glad we got the chance to go back together so soon. They are huge, but quite hard to find, actually, as they are hidden behind the hospital, and screened by the various barricades and fences that have been temporarily erected to control crowds attending concerts in the nearby park. It was a nice spot to linger and enjoy our lunch.

From there we headed down to the gaol and joined the 2 pm tour. I’m not sure there’s a lot more I can say about the gaol – I think I have shared most of my thoughts in the preceding paragraphs and in the captions to the photos below. But despite the grimmer aspects of the facility, when it was originally conceived in 1796 the designers had more lofty ambitions. Prisoners were to be given individual cells, and personal guards, who would help reform them – with the aim being that they wouldn’t became repeat offenders on release.

Sadly, these ideals didn’t last. A harsh prison governor was installed shortly after the gaol opened, and rising crime rates associated with the growing urbanity of Dublin soon led to over-crowding. Ambitions went out of the window and as many prisoners were packed in as possible. At one time it was housing nine times as many inmates as its design capacity. The situation was compounded by the Famine in 1845, which forced thousands to turn to crime in an effort to source food. And possibly even more to turn to crime in the hope of being convicted – because at least in gaol you were regularly fed.

I was surprised to learn that in the early 1800s, there was no lower limit for internment – the youngest inmate was probably just three (yes three) years old, and was sentenced to 14 days imprisonment for begging on the streets of Dublin. Women were also frequently incarcerated – and hanged – alongside men. Political prisoners started to feature in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – not just as a result of the 1916 uprising, but also as a result of the five failed uprisings which preceded it. Although many were imprisoned, most were eventually released – generally only a few unlucky ringleaders found themselves heading to the gallows or in front of the firing squad.

The vast majority of the people who passed through the cells were common felons, and generally they didn’t stay long. Custodial sentences were usually less than a year, so many soon found themselves back out on the streets. The longest serving inmates were usually debtors – they were supposed to be held until they could pay off their debts, which was often many years.

After the 1916 uprising and the elevation of the fourteen executed leaders to martyrdom, the prison gained some reverence in Republican eyes. However, this reputation was tarnished during the Civil War of 1922-23 when Irishmen were executed by fellow Irishmen simply for being on the wrong side of the Free State / Republican divide. As a result, once the war finished and the final political prisoner – Éamon de Valera – was discharged in 1923, the Gaol was closed down. It remained abandoned and falling into disrepair right until 1960 – mainly because the Emergency (aka the second world war) created other priorities, and because of a shortage of funds meant there was no motivation to do anything with it. Perhaps more significantly, though, the unhappy memories related to its long history of incarceration and execution meant that there was no particular desire restore it but no real will to to pull it down either.

Eventually a party of volunteers formed in 1960 and set about trying to repair the decades of decay, and in 1966 parts were opened to the public. Today, it is run and maintained by the Office of Public Works, which pretty much, in my eyes, guarantees that it will be tastefully and skilfully done – and it is.

So – there you have it. I’m glad we have been though personally I don’t think I would want to go back in a hurry. But you can’t dodge these uncomfortable truths and it’s important to remind yourself from time to time that life hasn’t always been a bed of roses. No matter how difficult times might sometimes seem in 2022, I for one am immensely glad that I am visiting this part of Dublin in 2022, and not a hundred years earlier.

Today’s photos (click to enlarge)

Interactive map

(No map today)