Ireland day 0096. Sunday 02 January 2022- Metals

| Today’s summary | Took the train to Dun Laoghaire to meet Dublin Walking Club for a hike up the “Metals” to Dalkey Hill, then along to Killiney Hill and back down to Killiney DART station for train home. Val last night at work | ||||

| Today’s weather | Bright, sunny and dry. Light breeze. About 12C | ||||

|

|

||||

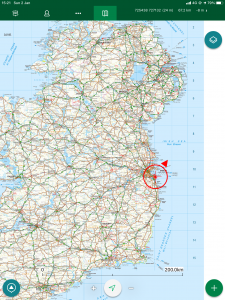

| Today’s overview location (the red cross in a circle shows where Val and I are at the moment) |

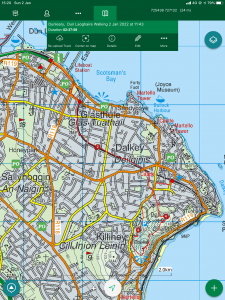

Close-up location (Click button below to download a GPX of today’s walk): Metals DWC |

||||

Commentary

We tend to think that “globalisation” is a phenomenon of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. But the longer I’ve been in Ireland, and the more I’ve learned about the history of the British Isles while I have been here, the more I have come to realise this is not the case. We already know that some of the earliest inhabitants of Ireland – the Celts – probably came here from the Mediterranean, and since then later invaders from England, France, Scotland and Scandinavia (the Vikings) have shaped the island. More recently I learned about the fascinating history of the Battle of the Boyne – where Ireland was really a pawn in a battle between England, France and the Netherlands and then in the early 20th century, how events in the Irish war of Independence influenced similar independence battles as far afield as India and Palestine.

But what has all this got to do with today’s outing to an unassuming suburb of southern Dublin? Well the walk today with the Dublin Walking Club (of which I am now proudly an official member, by the way – as you can see from the banner image at the top) was billed simply and intriguingly as “The Metals”. So I headed off to Dun Laoghaire on the train this morning – leaving Val at home, sadly, as she had one more night of work left at the Castle this evening – not really knowing what to expect.

Dun Laoghaire (which used to be known as “Kingstown” until it was renamed after the war of independence – the Irish name means “[King] Laoghaire’s fort”) used to be the main harbour for Dublin, and in fact until recently most of the ferries from Holyhead docked here. If you’ve ever visited Ireland with your car from the UK you most likely made your first landfall here – although now since the Liffey has recently been deepened and landward road access improved, most ferries arrive further upstream at Dublin Port.

But the reason that Dun Laoghaire rose to prominence is the result of two tragic maritime accidents in 1807, in which 400 sailors lost their lives. Following these shipwrecks, there were calls to build a safe “asylum” harbour which would provide easy and less hazardous access to the Irish Sea, and so prevent future accidents. The Scottish engineer John Rennie was commissioned to design a suitable harbour at Dun Laoghaire and deemed that two enormous piers would be needed to provide a safe haven. Work started in 1815 and continued until the 1840s. When they were finished, the two piers were each over a kilometer long, and enclosed the largest manmade harbour in the world. Even today the piers are amongst the longest in the world. The key question was of course where the rock to build these piers would come from and the answer lies in the Metals – subject of today’s visit.

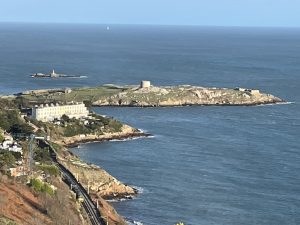

It was discovered that the rocky outcrop just inland from Dun Laoghaire – with twin peaks known as Dalkey Hill and Killiney* Hill – was composed of a suitably hard granite which would withstand the battering of the waves, and make a suitable building material for the piers. So quarrying at Killiney began and soon the digging operations had gouged out a massive chunk of the hill (as well as being used at Dun Laoghaire, the material was also used in the construction of the South Bull Wall, near Bull Island, and also exported to St Johns, Newfoundland – so the demand was huge). That left the problem of how to get the granite down from the quarry to the harbour, and this is where the Metals came in.

*By the way “Killiney” is actually pronounced “Kill-eye-ney”

Linguists will realise that the Irish name for the Metals (“Na Ráilli“) gives more of a hint about their purpose. In fact the Metals were a series of three funicular railways running one below the other in succession from the quarry down to the harbour. Trucks full of granite ran down the hill from the quarry on one set of rails (or “Metals”), and were connected by a looped metal chain to the empty trucks on the other set of rails, which were pulled up by the force of gravity acting on the loaded trucks going the other way. A brake on the chain at the top of the slope prevented the whole thing running out of control. The piers were finished in the 1840s but the quarry was operational until 1917. The Metals funiculars fell into disrepair sometime before that.

Anyway, after that long ramble, back to the global bit. If you look at the photos below, you will see that another oddly-named road – “Atmospheric Road” runs close the Metals. This marks the site of an even more peculiar railway – a vacuum powered line that ran near here from 1844 to 1854, linking Dun Laoghaire to Killiney by a 3km / 2 mi long “atmospheric” track. This unusual type of railway was pioneered in, of all places, Wormwood Scrubs prison in the UK, and the Dalkey railway was the first commercial line to this design of its type anywhere. The idea was so novel that it attracted interest from engineers all over the world. Brunel (of the Bray-Greystones line, among other things) copied it for his 30km / 20mi South Devon atmospheric railway, and the French engineer Mallet used the design to power the St Germain atmospheric railway near Paris for almost 20 years.

Ultimately, however, other forms of traction like the reciprocating steam engine became more economic and the Dalkey atmospheric railway was replaced by a “conventional” line in 1854. The DART line to Braystones and beyond today uses some of the old trackbed. It has to be said also that atmospheric trains suffered a more prosaic problem. The leather gaskets used to connect the carriages to the vacuum line were sealed with animal fat and the combination of fat and leather proved irresistible to rats. So the seals were rapidly digested by rodents, leading to frequent failures in the traction system, which were inconvenient and costly to repair.

Phew! Another dose of history. So how about the walk itself? Well it has to be said that pretty much every time I’ve been out with the Dublin Walking Club, the weather has been outstanding and my luck held yet again today. Although not quite as warm as yesterday, it still sunny pretty much all day, and it made for ideal walking conditions. We hiked out from Dun Laoghaire up towards Dalkey and Killiney Hills, admiring the impressive housing along the way (along with Howth, Killiney is one of the most expensive areas of Dublin). We joined the route of the Metals, which is now a footpath and cycleway, all the way up to the Killiney Quarry, where we paused for lunch and to watch the climbers scaling some of the high – and vertiginous – rock faces inside the quarry.

There’s a well engineered path up steps through the quarry, and out onto the summit of Dalkey Hill, with its Telegraph Tower. Then there’s a slight dip from there before you head back up to Killiney Hill, with the Obelisk on top, though really they are both just twin summits of the same outcrop. You can read more about the Tower and the Obelisk in the captions of the pictures below.

All the way along the top and then down again to Dalkey, the views are stunning and as you climb, traverse and descend you get a full 360° panorama from Dublin Harbour to the north round to the Wicklow coast and mountains in the other direction. So it was only a short walk, as we finished at Dalkey station rather than completing the loop back to Dun Laoghaire, but totally worthwhile. Who would have known how much history lay in such a small area, and what a hotbed of engineering innovation it turned out to be!

Today’s photos (click to enlarge)